Greetings stargazers!

I hope you have seen and enjoyed the planetary parade! It’s still happening in late February to early March, though Saturn is swapping places with Mercury, the former will be hard to see whereas the latter will become a little easier to notice in the next week or so. As for me, February’s skies were cloudy as usual but it seems we are now back in a run of clear nights. Less cold too, so more bearable for observing, but with winter’s constellations still sticking around a little, though Orion and Sirius set earlier each night. Giving way to the longer days and warmth of spring…

I am going to see if I can commit to doing at least a post each month, and I like the idea of a constellation per month. For now I’m doing the ones I didn’t cover in December’s posting spree, and those were mostly winter constellations anyway so from now onwards I’m going to cover those of spring and summer. Beginning with Hydra!

From now on I’ve decided to make my constellation posts a little more concise and practical, for those who actually want to look for and observe them. There will be some rambling about myth and science, but if you actually want to get to know the constellation yourself there’s nothing better than seeing it for yourself, so I’ll hopefully make that easier here.

Where I’ll really ramble will be if I get into multiple posts about a particular part of the sky that needs more depth because of the sheer amount of stories and/or scientific interest it contains.

To help, here’s a guide to each constellation guide, to begin:

What the constellation represents: pretty self-explanatory!

History: this is when the constellation was first documented. ‘Ancient’ refers to the constellations of the ancient Greeks, though many of these have roots in Mesopotamia and other older cultures. Newer constellations will have the century they were first named or the person who first named the constellation. For the most part I will be working with ancient constellations, but may go into newer ones.

Region of sky where it is located: this is where you can find this constellation, or what hemisphere it is best seen in. Equatorial constellations are visible in both hemispheres.

When visible? Time of year when it is easiest to see the constellation.

How visible? This is how bright and distinctive the constellation looks, and comes in four grades:

Very easy: well known with a memorable shape, and bright enough to see in moderate light pollution such as the residential parts of a city, or an urban park.

Easy: can be well spotted, even with some light pollution, can just about be made out in urban parks/gardens. Contains bright stars and/or a distinctive shape.

Intermediate: slightly harder to spot, best seen in suburban/rural skies or darker. Sometimes these constellations contain one bright-ish star though.

Advanced: a faint constellation that needs a dark sky to see.

Objects of interest: these are any interesting stars, galaxies, nebulas and other objects found in the constellation. Some, but not all, can be seen with a telescope or binoculars.

How to see it: this is a guide as to where to look for this constellation, usually by using other stars to help locate it.

Hydra

What the constellation represents: a mythical water snake

History: ancient

Region of sky where it is located: mostly equatorial, though in more northerly latitudes (like Europe and Canada) the southern parts of the constellation will be low in the sky.

When visible? Early spring, late spring. The constellation is so long that often parts of it are below the horizon. March-April is best for seeing it all.

How visible? Intermediate, best seen away from cities

Objects of interest: bright star Alphard, Southern Pinwheel galaxy M83, Ghost of Jupiter nebula

How to see it: Hydra is long and winding, but rather faint. The best way to find it is to look for Leo, who pounces out of the east at dusk on early spring nights. The distinctive Sickle asterism making the lion’s head and chest is the best way to find Hydra. Find Regulus, the bright star at the base of the sickle, and look downwards from there until you reach a medium bright star in a region with mostly faint stars. This bright star is Alphard, the heart of Hydra.

Hydra is not easy to spot in light pollution. In fact I’ve only seen the full constellation once, from a plane window, flying over Africa! A long, wiggly line of stars ending with a circlet representing the snake’s head, and one medium bright star in the middle. Even though this sinuous shape of stars is subtle, it looked impressive from high up in the stratosphere. Down on Earth, you might need to head to a dark sky area to check this celestial serpent out.

Alphard, the brightest star in Hydra, glows like a fading ember. This is an apt description, because this is a dying star, a red giant that is close to shedding its outer layers of gas as it reaches the end of its life-this is similar to what our Sun will face in billions of years time. Alphard, whose name comes from the Arabic for ‘solitary one’, is located 177 light years away. As of 2025, we’re seeing the light that left in 1848, the year Karl Marx published his Communist Manifesto and a wave of revolutions against monarchies swept across Europe. Make of that what you will when you gaze at this red star, especially in these current turbulent times…

Hydra’s history likely goes back to the Babylonians, where the constellation was often depicted as a great snake underneath the celestial Lion, and as I explained above, Hydra is right underneath Leo. These stars were associated with the goddess of chaos and mother of monsters, Tiamat. Marduk, king of the gods, destroyed Tiamat and sliced her in half, throwing both parts of her snaky body into the sky, where they turned into the constellations Draco and Hydra. A myth from India tells a similar story. There the sky serpent is called Vritra, who brought darkness and drought to the world, but was finally vanquished by Indra, the storm god.

If you know your Greek mythology, or have seen Disney’s Hercules, you will know the Hydra as one of the monsters that the famed hero had to face. First, a little reminder: Heracles-that’s the Greek name, Hercules is what the Romans called him-had to perform twelve labours, extremely difficult tasks that would mean certain death for most, many of which involved monsters that either had to be killed or overcome. Hydra was definitely one of the most formidable. A giant many-headed snake with poison blood, it was said that cows and people were killed by her deadly breath, and subsequently devoured. The monster was deemed impossible to vanquish-when one head was chopped off the Hydra, more would grow in its place. But Heracles knew that in order to stop that happening, he had to burn the bloody stumps where he had decapitated the serpent, and then cut off the ‘master head’ to destroy the beast once and for all. And of course, he did so. The dreaded Hydra was then placed in the stars, but with only one head instead of many.

There is another story associated with Hydra that is a lot less violent, a fable that also brings in neighbouring constellations, Corvus the Crow and Crater the Cup. In it, the sun god Apollo asked his pet crow to send him a cup full of water. The bird grabbed the cup and flew to a river to fill it up, but was distracted by a nearby fig tree, and proceeded to feast on its plump fruits. The crow forgot his original assignment and flew back to Apollo with an empty cup. When questioned, the bird said he had been distracted by a water snake, fearing that he would be eaten. So Apollo asked the snake if this was true, and she replied that she had not threatened to eat the crow. The sun god cursed the crow for his lies, scorching the bird’s throat with eternal thirst that could never be satisfied. This explains why crows have harsh voices! The story was immortalised in the sky with the snake, crow and cup placed close to each other as constellations.

In Chinese astronomy, Hydra represents a few constellations, including the head of the Red Bird, a great constellation that represents the southern skies, with Alphard known as Niao, the Bird Star. Another asterism formed from stars in Hydra was called Liu, the Willow. Because of their weeping branches, willows were associated with mourning and rebirth.

In 2017, the scientific community rejoiced at the discovery of gravitational waves. These ripples in the fabric of space-time are caused by some of the most dramatic and energetic events in the universe. Like two neutron stars colliding. In a galaxy located in Hydra, two of these small but extremely dense objects, the leftovers of supernovas, merged to become a black hole. This produced a great flash that outshone all the stars in that galaxy, and caused space and time to reverberate1 . The gravitational waves from the collision (which are tinier than the width of an atom) were picked up by the ultra sensitive Ligo detector in the USA, and backed up with observations by telescopes that saw the light from the same explosion. This is a brand new way of looking at the universe, combining optical observation with gravitational wave detection, which could help us make sense of some of the most powerful events in space.

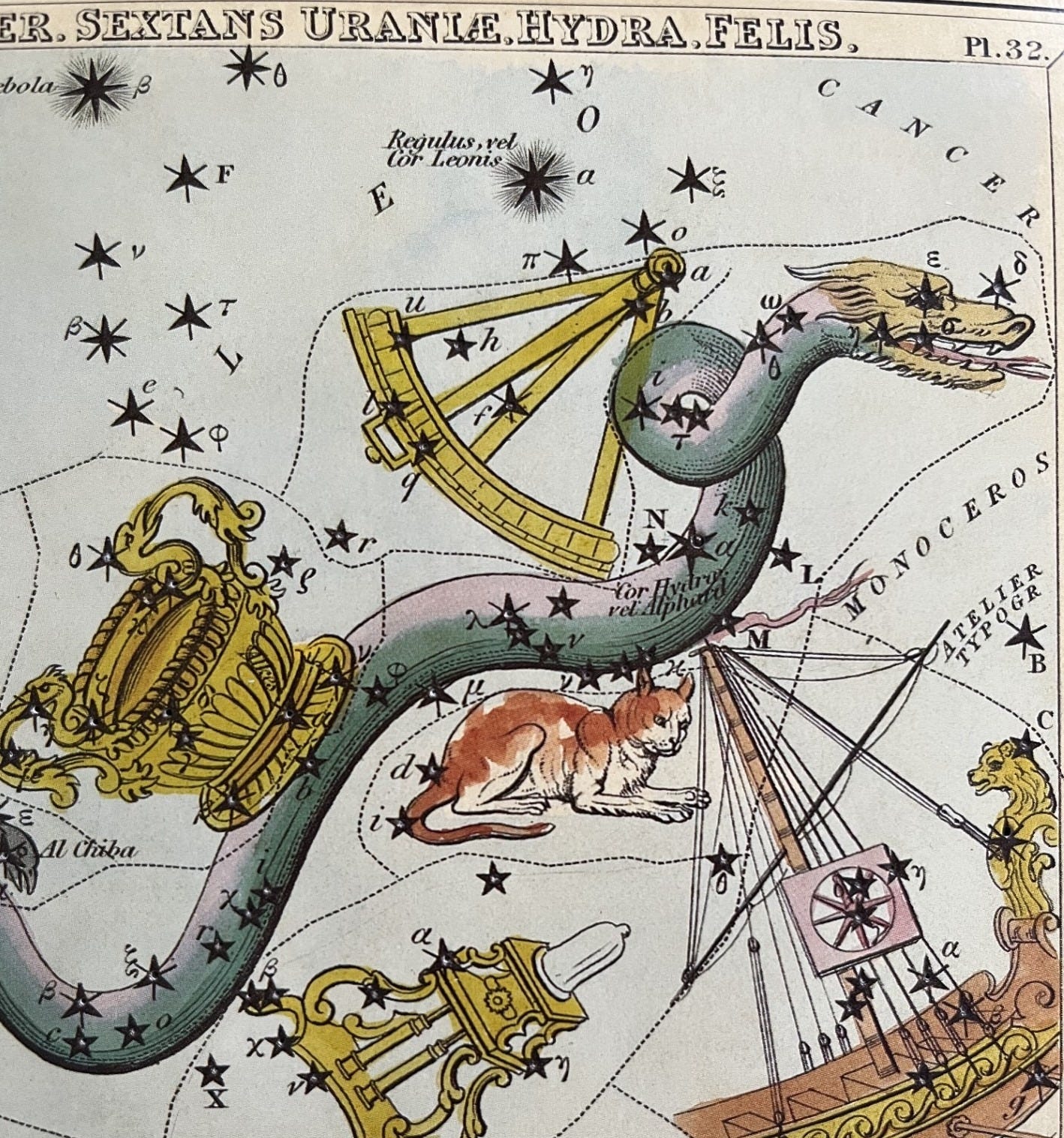

This constellation has another claim to fame: it is the largest constellation in the sky! So long in fact that at one point, some astronomers centuries ago tried to break it up with some whimsical asterisms that sadly didn’t make it into the ‘official list’ of constellations. These include Felis the Cat, invented by the French astronomer (and cat lover) Joseph Jerome de Lalande. As a fellow ailurophile, I am disappointed that one didn’t make the cut!2

Though seen as monstrous in the past, I like to think of Hydra as a harbinger of spring. Subtler than the glorious rise of Leo or the appearance of Arcturus, the brightest star of spring, Hydra gently surfaces from of the horizon like the first flowers. I sometimes reimagine it as a great wiggly worm, or sticking with reptiles, perhaps it is a slow worm3, the closest I’ve seen to snakes in my neck of the woods. You might have heard of March’s full moon as being called the Worm Moon, which I think corresponds well with Hydra being well placed in the sky and underneath the Moon at the time.

One way of looking at this constellation and the snake symbolism is the idea of ‘shedding one’s skin’ and being renewed for a new season. As the weather warms, we divest our thick layers of clothes and change our wardrobes. Out with the big jackets and sweaters, in with t-shirts and lighter fabrics. We also shed our ‘winter selves’ as we get ready for spring. Snakes and other reptiles spend their winters in ‘brumation’, similar to hibernation, and as the weather becomes warm enough they stir from their seasonal slumber. And as we approach the equinox and the days lighten, we prepare to release ourselves from winter’s heavy dark and into the light once more. We don’t need to rush though. Like the first shoots, or animals readying themselves for the new season, it’s best to do this gradually. After all, a snake probably feels quite vulnerable at first after shedding old skin and exposing new scales to the outside.

You might want to think about what you want to release as we begin the journey into the lighter half of the year. Shedding and release is often seen as an autumnal thing, like leaves falling from trees, but I think of both equinoxes as times to think about what we no longer need and whether to keep it or let it go. This is, after all, the season of tidying up, the ‘spring clean’. What parts of your winter self do you want to leave behind? Is it something to put away for next winter, or something to dispose of and consign to the compost? Are you ready to shed that skin and show another self?

Sources and further reading

Stars by Mark Westmoquette, Leaping Hare, 2020

Myths and Constellations by Mila Fois, Meet Myths, 2023

Constellations by Govert Schilling, Hachette, 2019

Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales: Hydra

Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales: Felis

Such collisions are the source of heavy and precious metals including gold. That gold in your jewellery, or in your electronics, was formed when the dense remnants of once mighty stars spiralled inwards and merged, their kiss making the universe ring…

In 1930, 88 constellations were approved by the International Astronomical Union for use on star maps and astronomical observations.

Not a snake, but a legless lizard!

Another great read and thanks.

Hydra will be a new constellation for me, I shall be searching for it. Really enjoyed reading about the voices of crows.